You won’t close many advertising deals without being asked to cut your price. But doing so takes away from revenue, sales commission and profitability – and that’s the best case.

More likely, it will make the deal harder to close – creating more obstacles and potentially sending your prospect into the arms of the competition.

That’s because most price objections aren’t really about price; they’re about uncertainty. It’s similar to when someone says he’s too busy to meet with you. It’s not that he doesn’t have time; it’s that your meeting isn’t important enough for him to push something else – work, lunch or leisure – off the to-do list. Your job is to get that meeting anyway, and many salespeople will do it by pestering the prospect until he or she finally gives in.

That’s because most price objections aren’t really about price; they’re about uncertainty. It’s similar to when someone says he’s too busy to meet with you. It’s not that he doesn’t have time; it’s that your meeting isn’t important enough for him to push something else – work, lunch or leisure – off the to-do list. Your job is to get that meeting anyway, and many salespeople will do it by pestering the prospect until he or she finally gives in.

What good can ever come from a relationship built this way?

When someone says the price is too high, that really means, “I don’t understand why I would pay that much for what you offer.” Lowering your rate is the “be a pest” solution; you may as well say, “You’re right – even I think it’s too expensive. So would you pay this much?” The lower you go, the less value your product has in the mind of the prospect.

Or you can make it your job to help him see why your product is worth the price. This is harder. Prospects don’t always put much thought into why they’re uncomfortable; they just know they aren’t at “yes” and price is the easiest way to express it.

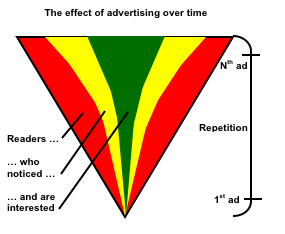

So you need to bring along the prospect on an examination of the value of advertising and specifically your product. It’s real work, but when done well, it results in a higher closing percentage, higher rates and better customer relationships.

Discuss price early

A salesperson’s instinct is to hold off on price conversations until the end of the sales process. But price negotiations are, by definition, adversarial: One side’s gain is the other side’s loss. So this strategy sets up the very last moment of the deal – when everyone should be feeling warm and fuzzy – to be its most contentious.

Putting price on the table early makes the rest of the conversation more comfortable.

I have a specific way of doing this, saying something like: “Businesses in your category generally go with a quarter-page ad, which costs $210 a month – or just over $2,500 a year – if you follow the best practice of running every month.”

Each part of that statement has a purpose:

- Suggesting an appropriate ad format establishes familiarity and expertise in working with your prospect’s peers. Be realistic; don’t suggest a large ad for a business that ought to be running a small one.

- Providing both a monthly and annual number creates a realistic benchmark of what a reasonable advertising program costs while letting your prospect digest the impact on cash flow.

- Asserting the need for frequency starts negotiations with an ad program that’s most likely to really work.

This early in the sales process, a prospect will usually withhold any meaningful reaction to the number – but it allows time for him to process any initial sticker shock.

If a prospect does push back you can address it directly by saying: “Without getting too far ahead of ourselves, do you have a specific number in mind for what this is worth?” (If you are a student of sales tactics, this is not intended as a trial close; this probing and should not lead to a protracted discussion of price at this time.)

Your prospect has three possible answers – any of which will provide useful insight:

- An unreasonable response. “Give it to me for a dollar and I’ll sign right now.” You’ve learned you aren’t being taken seriously yet. You have to spend time building trust and educating – probably over several interactions – before you’re likely to close a deal.

- A specific response. “I was thinking more like $160.” This is a sign the prospect is educated, has a budget in mind, and is sincere about wanting to buy – from you or someone else. You’ll want to emphasize the value of your publication and the professionalism you bring to the transaction – all while trying to find out where else he’s looking and leaning. (Don’t assume your competition is necessarily another publication like yours; it could cable TV, card packs, Angie’s List or some other media.)

- No response. If the prospect admits he doesn’t really know how much your service is worth, then the initial price objection is probably either a reflexive response to sticker shock or a sign he really doesn’t have enough money. Engage in conversation to find out more about his level of experience with advertising.

Once you’ve gotten through this part, you can set price aside and proceed with the usual steps of the sales process:

- Understand the client’s desires/motivation for advertising

- Educate about your product

- Create a direct connection between his desires and your product

Understanding the objection

When it’s really time to close, the prospect may again push back on price. This still probably means something other than “I won’t buy unless you cut the price.” You’ll need to probe to figure it out. Some possibilities:

I don’t believe in your product: There might be a disconnect between what you’ve told him and what he already believes. Perhaps he doesn’t see people reading it around town, or has heard others complain about lack of results.

I don’t understand it: The prospect might be unfamiliar or uncomfortable with how his spending is going to deliver a meaningful return.

My competitors don’t seem to advertise in your product: This is difficult to overcome and is one of the few occasions I’ll offer a judicious price discount, saying something like: “I know we’re perfect for Realtors but I need a real market leader to show them the way. If you have the courage to be the first, I might be able to arrange some kind of discount as long as you commit to a full year.”

Only an idiot pays retail for advertising: The people who are most responsible for this attitude are the people who sell ads. The prospect assumes that you’re like every other ad rep he’s dealt with: Afraid to lose the deal, not very knowledgeable about your own business, and more interested in getting his money than delivering on his objectives.

So prove you’re different: Explain why your published rates are worth paying, and let the prospect think about it by “closing” him on a promise to talk to you the next time you’re in the area. Then leave. Nothing will give this prospect more respect for you than a demonstration that you believe in yourself and your product enough to walk away for now.

One publication is as good as the next: Nobody expects a Mercedes Benz to cost the same as a Ford. When someone insists you meet the lowest price of some other advertising outlet, he is overlooking all the engineering that’s gone into making your publication successful. Respond by educating him about what makes your publication better for advertisers.

I want to make sure I’m not overpaying: Sometimes, the prospect merely wants to make sure he’s not paying more than necessary. You can provide all the reassurance he needs by saying, unapologetically, “For the program you want, this is the best price I can offer.”

Explaining why your rates aren’t flexible

The most useful tool in dealing with price objections is the sincere knowledge that your rates are correct. If you have any doubt about this, you’ll find some way to broadcast it.

Armed with that confidence, here are some constructive responses to persistent price objections:

- Our rates are based on our cost of doing business, and they are competitive. I can’t cut them further.

- Holding all customers to our published rates gives you confidence that you’re getting a fair deal. There are no secrets or magic words to get a better price. Nobody gets a better deal than I’m offering you.

- Our customer list is no secret; we publish it every month and place 9,600 copies of it around the community. Why don’t you call some of them and ask if they are paying the published rate.

- The more ads you buy, the lower your rate will be, and the better your program will work. It’s that simple.

- Our best rate is reserved for our best customers, and I’ll tell you exactly how you can get it: Buy a 24x program and pay your bills on time. I guarantee you will have the lowest rate anyone ever pays – and an ad program people will notice.

Finally, for the hard case

Some people simply won’t budge until they’ve seen you bleed. If you’re really confident that’s what is happening, don’t just reduce your rate. Instead, insist on a deal where you both get something you want. Like: “I’m not able to do anything on the rate for a 6x package. But if you agree to buy 9, I might be able to get permission to slide you down to our 12x rate. If I can do that, do we have a deal?”

And yes, that is a trial close: Don’t give away anything until the prospect promises it will be enough to seal the deal.

Image courtesy of Jesadaphorn/FreeDigitalPhotos.net

business, you need to develop a competency at it. Here are some of the most common mistakes I see as small businesses go to market.

business, you need to develop a competency at it. Here are some of the most common mistakes I see as small businesses go to market.

Value-added is the currency of the new economy. The idea is this: You do business by giving people what they pay for, but you gain and retain customers by adding a little something extra on top.

Value-added is the currency of the new economy. The idea is this: You do business by giving people what they pay for, but you gain and retain customers by adding a little something extra on top.