You’ve received quotes for advertising from two publications or websites; one wants to charge $150 and the other $350. How do you know which is the better deal?

Creating an apples-for-apples comparison between different publications is difficult because it involves so many variables.

The most common calculation for this job is cost-per-thousand (CPM), which measures the amount of money it takes to reach 1,000 people. You can use it for any medium – broadcast, print and online. (But it won’t hold up if you try to compare one medium against another).

Here’s the formula:

CPM = Rate/(Circulation x .001).

So if an ad costs $250 and the publication’s distribution is 8,000 copies, the CPM is $250/8, or $31.25.

It’s a simple calculation, and it lets you compare the rates of different publications with different circulation sizes.

But it has limitations.

For instance, it only works when comparing rates in the same media channel – print v. print or online v. online. That’s because the economics to produce different media – and the results they generate – are so different. Even when using it to compare two similar offers, be aware of these complications:

Ad size: CPM for a half-page ad will be higher than for a quarter page ad in the same publication.

Frequency. The more ads you buy, the lower the price will be for each. That means a single publication will have a different CPM for every ad unit and every frequency rate. The Heights Observer, which offers a pretty typical rate structure, has 60 different CPMs depending on the size of the ad and the number of insertions you buy.

Page size: Move vexing, a quarter-page ad in one publication (The Wall Street Journal, for instance) may be much larger than a quarter-page ad in another (i.e. Reader’s Digest).

That’s why it’s helpful to take CPM a step further – CPM per square inch (CPM/i²). It’s the cost you pay for each square inch of space to reach 1,000 people. Here’s the formula:

CPM/(height x width)

This will get you closer to that apples-for-apples comparison between different publications. It’s still not perfect. The bigger the differences between two publications, the less relevant CPM/i² will be. But in such cases, it may be the only tangible link for comparing disparate ad products.

So what’s the best way to use CPM and CPM/i² to make advertising decisions efficient and painless?

Step 1: Decide which publications you’re interested in, based on who they reach and how you feel they’ll work for you. Then look up or request their rates.

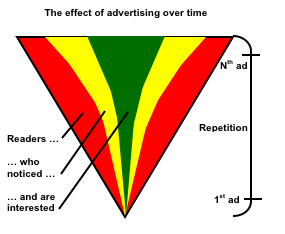

Step 2: After getting past the sticker shock, decide how much you want to spend per week, month or year. (Plan to advertise consistently over an extended period. It works best when treated as a long-term investment.)

Step 3: Select ad units in each publication that fit within your price range. Include any extra charges for color. If you can afford a full-page ad in one publication but only a small ad in another, that’s OK. CPM/i² should become a smaller part of your decision but it’s still instructive in your evaluation.

Step 4: Using the same frequency rate (i.e. if you use the 12x rate in one publication, use the closest thing to a 12x rate in every publication), calculate CPM/i².

Now you can evaluate the pricing with confidence, knowing this is as close as you’ll get to an apples-for-apples comparison.

In the end, CPM/i² is only one metric; it should never be the your only consideration. Such factors as a publication’s acceptance among readers, the relevance of its content and its customer-friendliness are at least as important.

Your gut may have to take you the rest of the way. But you’ll know there is at least some science behind the decision.

Image courtesy of Suvro Datta/FreeDigitalPhotos.net